Emigration.

Emigration was been part of life in the Sixtowns for over two centuries and hardly a household or family in the area has not been affected by it at some stage or other. Most went to America and of these , the bigger part would have made their home there. However many went to Britain, some for the potato or hay harvest on a short term basis , others to work in construction or in factories and spent the rest of their lives there. In an era of large families of ten to fifteen and only one heir to the farm, there was little choice for the majority of the rest but to emigrate. The departure of these young people in their droves must have torn the heart out of the community. Many were never to come back while others may have made the trip once when steamships made the journey across the Atlantic in a much shorter time.

Their stories were seldom told and they were rarely mentioned other than the fact that when they were out of site they were assumed to be doing well.One way or another the emigrant ceased to be part of life in the locality and so a huge part of our heritage was either ignored or never told. They would be referred to as Yankees, as if they had taken on a new nationality and a foreigner in their own land when they returned. Those who did not do well , the families were reluctant to talk about them. They were quickly forgotten. In the case of the successful emigrants, sometimes there would be a reluctance to believe their story at home or maybe, such matters had little relevance to the hard pressed people left behind in the Sixtowns. As well as that, in days gone by, stories were only passed on orally and they died with the passing of the tellers. With the emigration in such great numbers over the years, we would have to assume that many songs/poems or stories about the Sixtowns or its people were lost with the passing of these undoubtedly talented people.

It is very likely that a significant part of the heritage of the Sixtowns is either lost abroad or is lying in the drawers of cabinets in houses of second or third generation people from this area. Indeed some fine examples of this has already turned up which emanated from places abroad. Like buried treasure these artifacts and stories will keep turniong up as time goes on.

Emigration to the U.S.A. Why did these people leave in such great numbers?

In the early part of the 1800`s the population of the Sixtowns, like that of the rest of Ireland, soared. A large family could survive on a very small holding because there was a plentiful supply of the staple food, the potato, available since it could be grown on even poor land.

Most people from the Sixtowns who would have left for the U.S.A. would have headed for New York or Pennsylvania initially. These were strong men with few skills and therefore well suited to mining work or to working in the steel mills of that part of America. Women would have found work as housekeepers and other unskilled jobs. Since these people were coming from a farming background they would have few skills to take to the job market. On top of that there would have been a lot of discrimination against the Irish. Apparently this was the reason why most Irish Emigrants went to Western Pennsylvania and Maryland since there was less of it there. Many would Gaelic speakers with in some cases little or no English and this would have further hampered them in their new country.

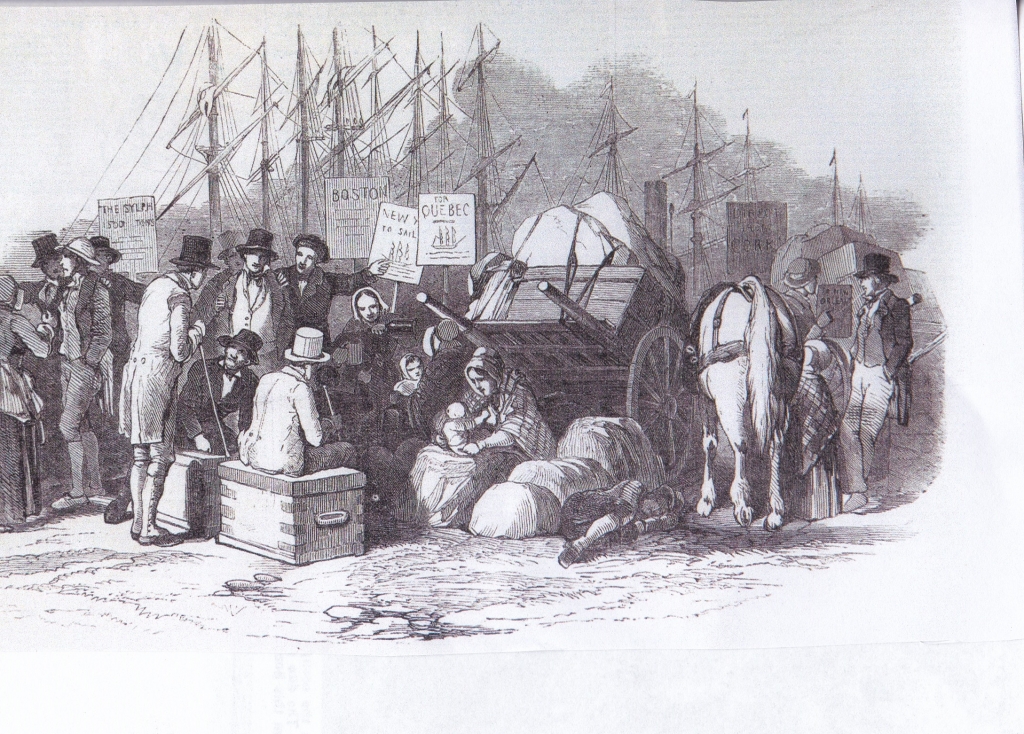

Those who were successful in making a new life for themselves would send on the fare to other members of the family, who would follow their footsteps into exile, and it would be their obligation to help the next ones to come out, thus creating a network of assistance to emigrants coming out. This tradition continued right up until the 1950s. No one knows the hardship and the trials which these people came through, especially the earlier ones. On the eve of someone emigrating an Irish wake or “convoy” as they were called in the Sixtowns, would be held and the people would gather to comfort the emigrants on their last night with their loved ones or to give them gifts of oatmeal or anything which they could afford to help them on their journey. There would be a dance and songs would be sung to keep the spirits of the emigrants up. The singing and dancing would continue until the dawn. Sad farewells would be bade in the morning, for it would be the last time many of them would see each other ever again. This was why they referred to nights like this as the `wake`. Some of the family or friends would walk a small part of the journey with the pilgrims before bidding their final farewells. The next ordeal was to walk to Derry and wait for sometimes weeks for sailing conditions to enable the ship to set off. The old people used to talk of lines of emigrants sitting along the quay at Derry, boiling their porridge or spuds in little skillet pots as they waited. Then there was their last sighting of their dear homeland as the ship sailed west past Fanad point, on the coast of Donegal. Next they had to survive up to eight weeks on the sea, with sea sickness and the dreaded fever for ever looming on the horizon. The old sailing ships would have been cramped and uncomfortable to travel in and if sickness broke out on board it quickly spread to other passengers because of the lack of ventilation or the cramped conditions. If a person died during the journey, their body would have been thrown overboard to a sea burial. The worst period of fever would have been during the famine when a huge amount of passengers would have been already suffering from malnutrition and other forms of illness before boarding atall. These were known as the “coffin ships” for obvious reasons. There is no doubt about the terrible exploits of passengers on these ships. It is not known how much the people who left the Sixtowns were affected by this phenomenon but one James Gillespie from Tullybrick wrote about taking the fever on the journey over to America and being lucky enough to survive it. However, not all the passages over were as perilous and many passengers were passed fit and healthy when they passed through Ellis Island or Statten Island which were the quarantine stations for newly arrived immigrants. Passengers seemed to stick together in groups for security and company on their journey. They would cook their food on the deck and they would pass the nights away huddled in groups listening to the music of a fiddler or singer. When they would arrive at the other side you would expect their ordeal to be more or less over, but for many it was only starting. A newly arrived immigrant, most likely a Gaelic speaker with no English and no work skills, would find it very tough surviving particularly if the winter was coming on. For many, they were worse off than they were at home. There they would have their food, (barring famine years) and they would have their people around them. The Irish were bottom of the pile in terms of opportunity and employment and they were left to fight it out with the Black people for the most menial jobs. This eventually led to rioting in New York city in the early 1860`s. Some buckled under the challenge while others dug deep and showed remarkable resilience and courage to make a life for themselves in their adopted country .For many who could not make out any other way, the army provided shelter and food when starvation would have been the only alternative. Many would get work in mines steelworks or on railways where the work was extremely dangerous with no concern for the safety of the workers. How many of the Sixtowns people ended up in these types of jobs it is not known but it can be assumed that many did. Many Irish disappeared after landing and were never heard of again. A young woman from Moyard disappeared on her way to America and was never heard of again. There is no doubt that the type of employment aforementioned would have provided an explanation for the disappearance of many others, as the lives of workers meant little to their employers in many cases..

There is the story about the young Bradley lad from Moyard who was out poaching on the mountain when he was challenged by the local gamekeeper, fired a shot at him, in order to make good his escape. When he arrived back to the family house his parents, were very annoyed at his actions, because he may well have caused them to be evicted . after having a heated argument with his parents he stormed out of the house saying, “Well, you will never have it to say again that I let the family down.” He went down to a house in Bancran where there was a convoy being held for some people who were going to America, joined them and the next morning he went to America with them. His family never heard of him again. We can only try to surmise what became of him but there would have been plenty of others from the area that would have had suffered a similar fate, such was the perilous road that lay ahead of the emigrant. There was one thing for sure in the early days of emigration and that was if you came across on one of those old sailing ships on such a perilous journey, going back home again was definitely not an option. The human being is at his or her best when they are being severely tested and in this case it made tough and resourceful people out of these raw emigrants. These people who left Ireland in the early days have long integrated into American life and are now difficult to trace because of the peculiar variations in the way they spell their surnames. This was done for various reasons. Some were uneducated and could not spell their names properly while others were translated directly from Irish.

Hugh Murrin`s story.

The earliest records of anyone having emigrated from the Sixtowns area to America is of a man called Hugh Murrin (now spelt Moran) who was born in the Sixtowns, most likely Tullybrick (which was then called Moranstown) in 1748. Hugh arrived in America some time in the second half of the 18th century. It is not known whether he had contacts over there or if he had been in the army and was posted there. If he had had some military experience then it was put to use shortly after he arrived in America as the Revolutionary War of Independence broke out he joined the New Jersey regiment and fought against the British.

At the end of the war trouble broke out with some Indian tribes over land and Hugh found himself part of an expedition sent to strengthen Fort Pitt. When his military career ended he married Catherine Shaw and the had eight sons. In 1796 Hugh bought a piece of land about fifty miles north of Pittsburg Pa. and began to farm. Around the same period as pioneers began to push west and north into the wilderness, new roads and railways started to advance out there to improve transport. It happened that one of these roads passed through Hugh`s land and he decided to take advantage of the passing trade.He decided to build a village just where there was a crossroads on his farm and advertise lots for sale. He built a house at the crossroads which he converted into an hotel for weary travellers. Later he built a one room store, a grist mill and a distillery. The village was called Murrinsville after its founder and is a flourishing town today. It is said that Hugh Murrin built a log church with a graveyard attached in the village in the early 1800`s. Later in 1842 he helped build the St. Alphonsis Church in Murrinsville and it was completed later that year.

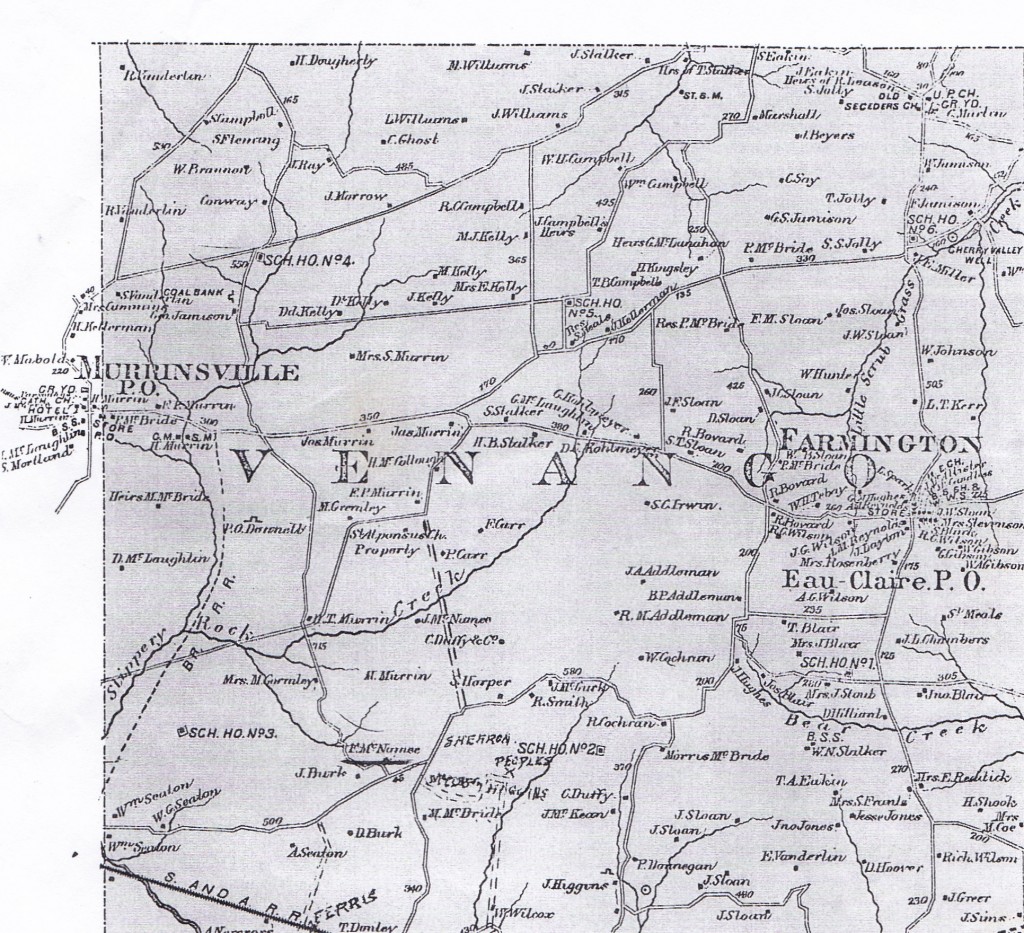

Hugh Murrin is known to have helped many of his kinsfolk and neighbours from the Sixtowns to settle in the Murrinsville area. One such family was the McNamee family who were close relations and whom he helped buy a piece of land shortly after arriving. Some descendents of that family have recently visited the Sixtowns to check up on their family roots. A map of Murrinsville district around 1859 shows the names of the landowners of that time and it is noticeable how many prominent surnames from the Sixtowns are to be found on it. Regrettably, many of the farms and their owners are gone from this area now because of extensive open cast mining for coal there over the last century. It is not known if there are many descendents of these farmers still in Murrinsville.

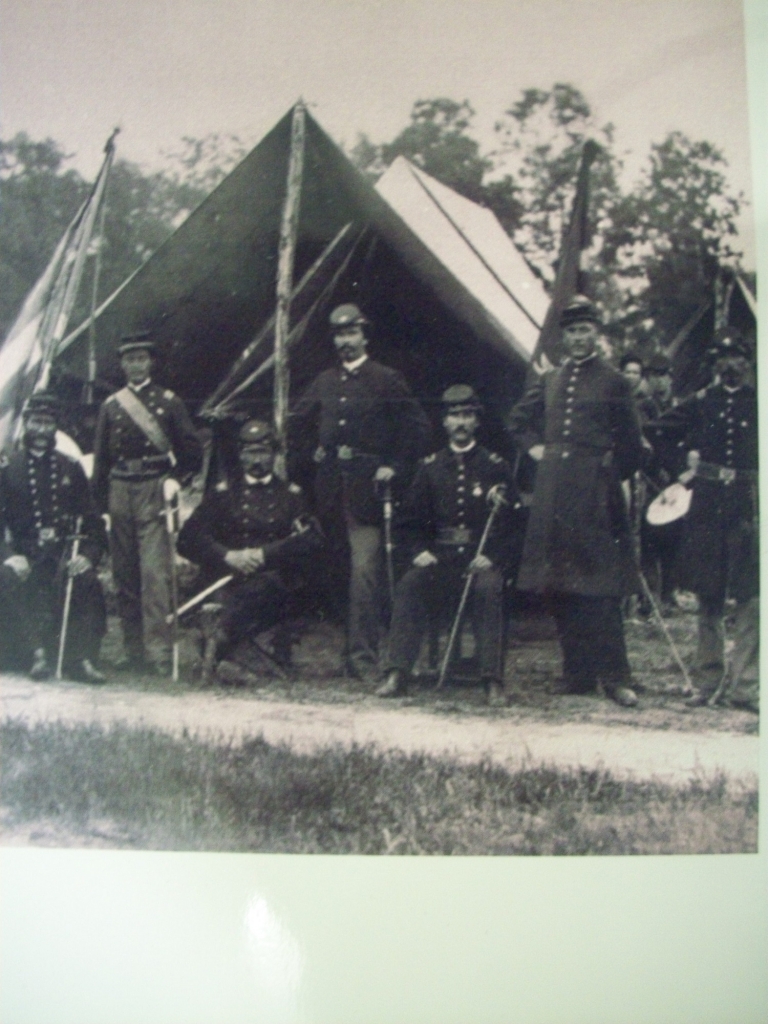

Emigrants from the Sixtowns area to America have made their mark militarily during the 19th century, with one Captain Charles McAnally being awarded the Medal of Honour (the highest military award) during the American Civil War. His brother, Sergent Peter McAnally fought in the same regiment. Captain Hugh Bradley and private James Gillespie. There undoubtedly were others from the Sixtowns who having emigrated in big numbers would have found themselves caught up in this conflict.

From Glenviggan to Gettysburg.

Captain Charles McAnally is on the extreme right of the picture.

Captain McAnally was one of three sons of Thomas and Elizabeth McAnally from Glenviggan. He was 19 when the family emigrated to Philidelphia in 1852. There Charles found employment in the grocery trade. When he reached the age of 27 the first rumblings of the Civil War were being heard across the country and as tensions grew men began to join up local militias to defend their areas if the need arose. Local businessmen like bar owners or hoteliers were usually elected leaders of these militias. Charles joined Captain Harvey`s Montgomery Artillery as a private soldier and was sent to guard Fort Mifflinn. It all must have seemed quite romantic for Charles at that stage. Little did he know how he would be flung into a most brutal and bloody war. He had come to America to look for a better life and like so many other emigrants found himself fighting for a country that was a long way from Glenviggan. Nevertheless he gave it all he had and although wounded many times survived where the most of his fellow soldiers in his regiment were killed or severely wounded.

When the Civil War did break out most of the various local militias were disbanded , reformed and amalgamated into the 69th Pennsylvania Regiment which was to make a name for itself for its bravery and fighting spirit in so many crucial battles of the war. This regiment was called on in so many battles to shore up faltering battle lines that it suffered huge casualties over the war to the point where the Irish stopped supporting recruitment of new emigrants because they felt that the 69th was bearing an unfair burden in battle. The end result was that the regiment was nearly wiped out towards the end of the war.

Charles McAnally and his brother Peter defied all odds and survived the war. He was wounded at the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 receiving a sabre wound to the head.

This monument was erected in memory of Father Colby, chaplain to the 69th Regiment, who famously gave general absolution to Charles, Peter and their comrades before they went into battle. This is the stone on which he stood.

The 69th lost almost half of its men in this savage fighting. Two Irish regiments fought against each other in that battle, the 69th regiment and the 1st Virginia who were on the Confederate side. Young Willie Michell, son of John Mitchell the Irish Patriot, who was only 17 was killed in that battle. It was testimony to the futility of war when two men, one from Dungiven and one from Ballinascreen should end up fighting each other on a battlefield three thousand miles from home.

Young Mitchel`s regiment started to march from this spot towards the 69th Regiment positions on Cemetery Ridge in the centre of the picture. Charles and Peter McNally were at Cemetery Ridge. Derry man against Derry man in a foreign land and far from home.

The 69th Regiment with which Charles was fighting were positioned on this horizon which was known as Cemetry Ridge. Thousands of Pickets Regiment marched to attack their positions from where the cannon is situated. The 69th famously held their line there and this bloody battle proved to be the turning point in the Civil War as the Confederates turned back to the south ending their drive to invade the north. The McAnallys would have taken part in desperate hand to hand fighting in this battle.

By the time the battle of Spotsylvania began on 12 May 1864, the 69th was all but decimated from constantly being thrown into the thick of the fighting in one battle after another and Captain McAnally and his brother were still alive and fighting. It is said that this battle saw the most cruel and brutal of the war and there were immense casualties on both sides. In the heat of the battle Charles was wounded as he captured an enemy flag but kept charging on until he received a second wound to the shoulder as well as buckshot wounds to his head and face. At the Battle of Cold Harbour on 2nd June 1864 the Federal army took 13,000 casualties and the wounded men lay out in the baking sun for three days because General grant would not ask for a truce as it would be admitting that he got a walloping from the Confederates that day. Grant believed in strength of numbers in overcoming the enemy and the result was that men were just thrown at the well entrenched enemy. Charles was shot below the knee in that battle and had to fight with surgeons to prevent them amputating his leg. After the battle he was promoted to captain and recommended for the Medal of Honour by his comrades for his bravery in so many battles. It does not bear thinking about the horrors that Charles would have witnessed throughout the war and undoubtedly they would have lived with for the rest of his life. However he was lucky to have survived as did his brother who was a sergeant in the same regiment.

When the war ended Charles got employment digging up the corpses of soldiers killed in the war and helping reinterring them closer to their loved ones. After this work finished he got married and tried his hand at farming in Texas for a while but it is believed that his old war wounds began to catch up with him and he became unable to work. He was still alive in 1914. He spent his final days in a home for old soldiers of the Civil War.

From Moyard to Pennsylvania and back.

Hugh Bradley

Hard as life was at home in places like rural Sixtowns, it still took immense courage and determination to leave one`s family and native land to face the trials and uncertainties of travelling such a long way to a land that was different in so many ways from anything they could have imagined. Nothing would have prepared these emigrants for what lay ahead of them. However, such is the nature of the human being that in times of great peril or seemingly unsurmountable obstacles, they can dig deep and rise to the challenges, drawing on courage and survival skills which they did not realise they possessed.

This was very much the case as a young seventeen year old Hugh Bradley, son of Roger and Mary Bradley of Moyard, headed for Belfast to catch a ship heading for New Orleans. With precious little money and no trade skills of any sort the prospects would not have been good for this young lad. However, drawing from stories of earlier emigrants doing alright when they reached the other side, Hugh, would have been giving himself at least a fighting chance. His story is documented in the History of Cambria County, Pennsylvania where he ended up living and working for fifty six years after arriving in America.

Apparently, he headed for New Orleans because he had family conections in St. Paul, Minnesota and he could take a steamer boat up the Mississippi river to reach his destination. As well as that ships tended to head for the southern ports of the U.S.A. in winter time so as to avoid the icebergs which floated through the northern Atlantic ocean.

Everything went to plan until the steamer snagged at Memphis, Tennessee and Hugh had to get off ending his trip and plans. He got employment for a year or so on a local farm doing the kind of work which he knew best. Then he got a job as a stevedore at the docks along the river loading cotton onto ships. At this stage he would have had to contacts to help him get work or a place to stay and must have been quite a resourceful young man to have survived. This is where the raw immigrant would buckle to the pressure or else dig deep, stand up and fight for their survival. It would have been the typical situation which any immigrant of the day should expect to find him/herself in. After working there for a while Hugh happened to meet a locomotive engineer called Frank White who took a liking for this young Irishman and gave him a job as his fireman on the Memphis and Charlestown railroad and indeed his first trip was on a new stretch of line from Memphis to a town called Moscow. As they would have said in those days, he pulled the first throttle on that line which is still there today.

After working long enough on the railway to be able to look after himself young Hugh felt the draw of northern Pennsylvania, where he had family conections. In May 1853 he left and made his way to Johnstown, Pa. stopping for a couple of weeks in Pittsburg probably with people he knew from back home. He spent time afterwards working as a puddler in Phoenixville, Chester County near Philidelphia where a lot of Sixtowns people would have settled.Working as a puddler was a very tough and dangerous job where the workers had to work in extremely hot and smokey conditions clawing the impurities off the top of the huge furnaces of molten steel in the Ironwork factories. The pay would not have been good but many Irish were glad to get work of any kind at the time. After a short period Hugh moved to work in the Cambria Iron Company in Johnstown, where he would remain until he retired in 1905. He lived at 60 Market St. Johnstown close to his work.

(LEFT)

A much changed Market St. Johnstown where Hugh lived.

He only had two breaks in his working career with the Cambria Iron company. The first came in 1861 when President Lincoln called for seventy five thousand volunteers for three months “to suppress treasonable rebellion”. On the 18th April he enlisted, as did so many immigrants like him at the time, in Captain John Linton`s company of the Third Pennsylvania Volunteer Company.

Soon after he was promoted to first lieutenant. His main involvement in action at first was in Virginia but later he was called into action in Pennsylvania when there was the threat of a Confederate invasion of that state. However, Hugh was luckier than his fellow Sixtowns men like the McAnallys who were at the cutting edge of the fighting throughout the war. General Lee`s plan was to reach Harrisburg but his army was stopped at the battle of Gettysburg and this meant that Hugh`s regiment avoided most of the fighting.

This Johnstown Pa. where Hugh lived and worked for 50 years. The site of the iron works is at the bottom left of the picture.

Hugh`s second break in service at the Cambria Iron Company was when he realised the life long desire of the immigrant to visit his homeland. Many never saw their homeland or families after emigrating but some were fortunate enough to be able to make the trip, if only once. The prospects of making such a trip became more possible with the advent of the steam ship and in June 1899 Hugh Bradley made the trip home to the old sod after fifty years to find that his mother and father were dead as well as many of his childhood friends.

This was the lot of many such emigrants who never lost the dream of once again returning to their native homeland only to find that time had made huge changes from the day they left and they were near enough strangers in their own townland. Many would return to America like Hugh with a mixture of emotions but never feel the urge to return again. Therein lies the sentiment behind manys the emigrant song or the thoughts being exchanged at the final handshake or kiss when that person sets off for the ship for America in those times. Hugh returned to Johnstown where his family lived and he died on the 1st April 1909.

This is the grave of Hugh Bradley in St Mary`s cemetery in Hollidaysburg Pa.

On the left is the grave of his third wife, Catherine.

He was married three times. His first wife was Mary Riley by whom he had seven children. She died in 1880 and later he married Mary Bradley and she died after only two years. He then married Katherine Blatte who was the daughter of an German immigrant. Of his seven children, one would become very famous indeed in the gambling and horse racing circles across America. He was known as Col. Edward Riley Bradley and was the owner of several prominent gambling establishments as well as being a famous race horse breeder and owner of the Idle Hour stud farm in Lexington, Kentucky.